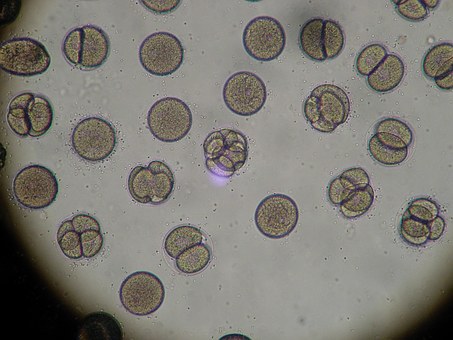

It is now becoming well understood that with chronic infections, such as CRS, bacteria have the ability to form an organic matrix made up of polysaccharides, protein and even DNA. However, to say that this organic matrix forms a protective shield for the bacteria is a gross understatement. Instead of a shield this organic matrix or glycocalyx behaves more like a 16th-century fortress able to withstand months of an enemy’s siege.

According to John Costerton’s work in 2003 on bacterial biofilms this glycocalyx is a mosaic of bacterial colonies that possess varying phenotypes and different physiochemical properties. Not only does this protect the bacterial inhabitants, but it also serves to modulate the microenvironment of these colonies through its numerous canals via a process of interbacterial signaling called quorum sensing.

Just like in the Siege of Vienna of 1529, Viennese defenders were able to detect the subterranean activities of the Ottoman sappers and miners who were attempting to blow up the cities walls with large amounts of gunpowder. The defenders were able to sink counter mines in the precise locations trapping and killing many of the enemy. This is ferocious stuff, but no less ferocious than the war that is going on the sinus cavities of those suffering from CRS.

Just like in the Siege of Vienna of 1529, Viennese defenders were able to detect the subterranean activities of the Ottoman sappers and miners who were attempting to blow up the cities walls with large amounts of gunpowder. The defenders were able to sink counter mines in the precise locations trapping and killing many of the enemy. This is ferocious stuff, but no less ferocious than the war that is going on the sinus cavities of those suffering from CRS.

This is quite the departure from the conventional thinking of chronic infection therapy from when I was training in infectious disease. Back then, it was thought that bacterial infections caused by isolated bacterial types that would respond to antibiotic therapy. Unfortunately, as time goes on and more and more patients fail conventional therapy, it is becoming better understood that bacterial behavior is much more complex in chronic infections than initially thought.

One important breakthrough for understanding the complexity of chronic infections is more advanced testing for bacteria than what was previously available. Even up until today, many clinicians rely on the old Pasturian method of detecting which bacteria is causing infection; however, in many instances, the one species may have dominated the culture, therefore, missing other organisms that could be contributing to the process. Today we have molecular DNA analysis to help us determine the causative agents.