Over the past several years medical research is beginning to understand the association between Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) and chronic inflammatory states. This is the first in a series of articles dealing with the subject by Sandeep Yerraguntla, a UGA student looking to pursue a career in medicine.

Connective tissue is one of the four basic animal tissue types that develops from the embryonic layer known as the mesoderm and is known to support and protect organs. Areas of the body including the bones, tendons, ligaments, cartilage, fat, and blood are composed of connective tissue. The presence of this tissue confers strength and elasticity, and holds strong proteins that allow tissue to be stretched but not beyond its limit. The components of connective tissue include cells, protein fibers such as collagen and elastin, and a ground substance. Collagen is the most abundant protein in mammals that promotes flexibility and elastin is another major connective tissue protein that makes up most of the skin and ligaments. The combination of collagen and a ground substance form much of the extracellular matrix, which is a network of non-cellular components that provides structural and biochemical support to a cell.

A group of disorders that affect collagen and elastin production, and thus weaken the connective tissues is known as connective tissue disease. In patients, collagen and elastin are usually inflamed and there can be subsequent abnormal immune system activity as a result of an immune system targeting one’s own tissues, which is known as autoimmunity. Connective tissue diseases can manifest through inheritance patterns or environmental factors such as infections, inadequate vitamin D or C levels, or exposure to UV radiation, just to name a few. There exist over 200 types of connective tissue disorders with symptoms displayed from different parts of the body such as bones, joints, skin and blood vessels.

One rare genetic connective tissue disorder is Ehlers Danlos syndrome (EDS), characterized by joint hypermobility, skin hyperextensibility, and tissue fragility. The two studied inheritance patterns for EDS include both autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive inheritance. Symptoms can vary from mild, undiagnosed to potentially disabling. In the joints, we observe hypermobility, joint pain, loose and prone to dislocations, and onset of osteoarthritis. In the skin, we observe soft, velvet-like texture, skin fragility and easy bruising, severe scarring, poor wound healing, and cases of molluscoid pseudotumors (fleshy lesions with scars). Less common symptoms include chronic musculoskeletal pain, arterial/intestinal rupture, poor muscle tone, scoliosis, early disc degeneration, and gum disease.

Because connective tissue is widespread in the body, EDS can manifest at different locations, so we have seen 13 subtypes of EDS with significant symptoms. Examples include Classical (cEDS), Vascular (vEDS), and Hypermobile (hEDS). Patients with cEDS experience wounds that split open with little bleeding and leave scars that widen over time to create characteristic “cigarette paper” scars. Patients with vEDS experience unpredictable rupture of blood vessels and organs, which could lead to internal bleeding, easy bruising, or stroke. Patients with hEDS, the most common form of EDS, experience mostly joint hypermobility.

In addition to limb defects, EDS may be linked to nervous system disorders. EDS patients may complain about headaches resulting from migraine, muscle tension, or hypertension due to poor blood flow to the brain. One specific nervous system complication with EDS is idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), which is associated with an increase in fluid pressure under the skull. An increase in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) production or decreased absorption can cause a net increase of fluid pressure on the brain. Symptoms include headaches, nausea, light sensitivity, and vision changes. Approximately 93% of affected patients have narrowing veins under the skull. More research must be conducted on the specific link between IIH and EDS, which can answer how IIH manifests in EDS patients and whether treatments for IIH are effective in the EDS population.

Another nervous system disorder that may be associated with EDS is chiari malformation (CMI) which has been observed in patients with hEDS. CMI affects the tissues around the brainstem resulting in obstruction of fluid movement in the brain. Effects can be hormonal as obstruction in fluid can flatten the pituitary gland. It is difficult to manage both EDS and CMI due to the head and neck area being overly mobile.

In our practice we have several patients which have been diagnosed with either IIH or CMI that demonstrate traits of chronic inflammatory response syndrome (CIRS). The association between EDS and CIRS will be discussed shortly.

In order to diagnose EDS by itself, we take note of patient history and clinical findings. Genetic testing will help determine ED subtype diagnosis and possible gene mutations, and specialized testing includes MRI and echocardiography to detect cardiac abnormalities (e.g. mitral valve prolapse). For a physical diagnosis, the Beighton score is used, which is a screening technique involving a 9 point scale with 5 maneuvers to determine hypermobility.

In order to treat EDS, the focus is on preventative measures to reduce complications in the musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, and integumentary systems. Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) is recommended to help reduce the easy bruising, and strenuous exercise should be avoided due to the risk of joint trauma. Physical therapy and low-resistance exercise are recommended in addition to calcium and vitamin D supplements to maintain bone density. Patients should have regular screening for hypertension and arterial disease, which are known complications of blood vessel fragility. Surgery may be an option to repair damaged joints or blood vessels. A more recent intervention, prolotherapy is a type of regenerative medicine that involves injecting a solution containing dextrose (a sugar), glycerin, lidocaine/procaine, or growth factors in order to strengthen connective tissue of joints tendons, and ligaments, and case studies have shown prolotherapy to be an effective procedure.

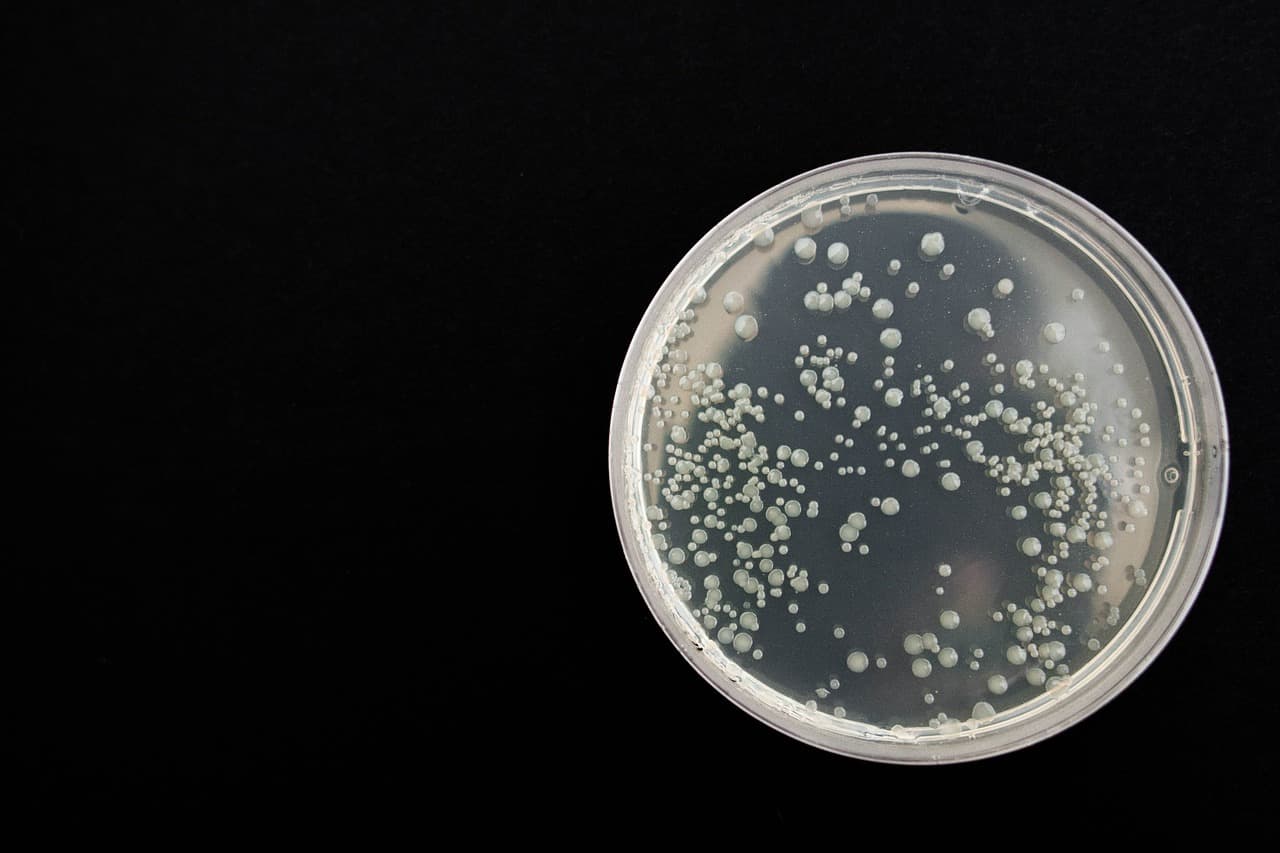

Chronic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (CIRS) is a multisystem illness acquired from exposure to biotoxins such as mold. The inflammation is non-specific and can affect any body organ system. It can develop after chronic exposure to water-damaged buildings due to residual microbial growths: bacteria, molds (fungi), mycobacteria, and actinomycetes.

CIRS results in the activation of the innate immune system and dominant clinical features include cognitive difficulties: brain fog, memory loss, and loss of executive function. Usually, mast cell activation syndrome is associated with CIRS in response to biotoxin exposure. Mast cells (MCs) are innate immune cells that secrete inflammatory chemicals such as histamine and cytokines when exposed to harmful agents. They are involved in the allergic response, nerve disorders, and connective tissue defects.

Mast cells are involved in Ehlers Danlos. To begin, body cells are supported and anchored by an extracellular matrix (ECM) that is usually composed of collagen. Collagen deficiencies play an important role in EDS since MCs are known to adhere to proteins in the ECM, which can modulate MC behavior. Thus, an altered ECM in EDS patients can lead to abnormal/upregulated MC behavior. In fact, one study links a shared mutation among a triad of diseases: EDS, MCAD, and Postural Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS, lightheadedness and rapid heartbeat upon standing). Mast Cell Activation Disorder (MCAD) refers to the increased activity of MCs activity. If left untreated, it can develop into autoimmune conditions. In EDS patients, this can lead to increased permeability of blood vessels, smooth muscle contractions, heart palpitations, increased mucus production, and congestion. Triggers for MCAD include alcohol, drugs, invasive procedures, fever, or stress. To diagnose MCAD, blood and urine samples are tested for molecular markers or chemicals associated with MCs such as serum tryptase, histamine, prostaglandins, heparine, or small gut samples.

Having both EDS and MCAD together should not affect treatment regimen. MCAD is incurable as of now, and figuring out the symptom triggers is important, so the frequency of activation is decreased. To help with fatigue, patients should exercise regularly, but avoid overexertion and find ways to reduce stress. Drug treatments should be specific to individuals: antihistamines H1 and H2, sodium cromoglicate, ketotifen, omalizumab are effective. Aspirin and ibuprofen can help with pain, but it depends on the patient. Lately several patients have responded well to low dose naltraxone.

We are only now beginning to understand the association between chronic inflammation and genetic predisposition. What is known as that as healthcare improves we will see more genetic diversity in the world population. This increase in genetic diversity will lead to more unusual and atypical presentations especially in those dealing with chronic inflammatory disease. In order to help these patients not only research is need but a greater understanding of individualised therapies because a one size fits all model will not work well when dealing with chronic inflammation.